import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import seaborn as sns

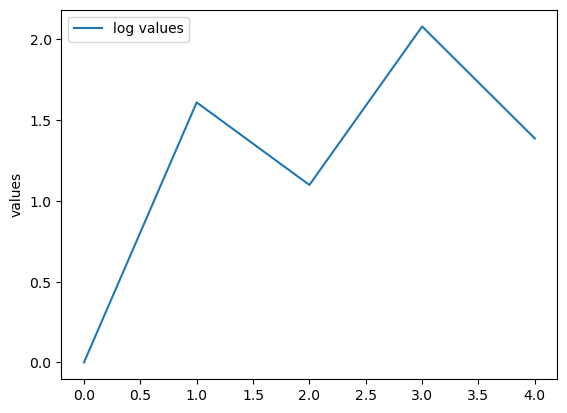

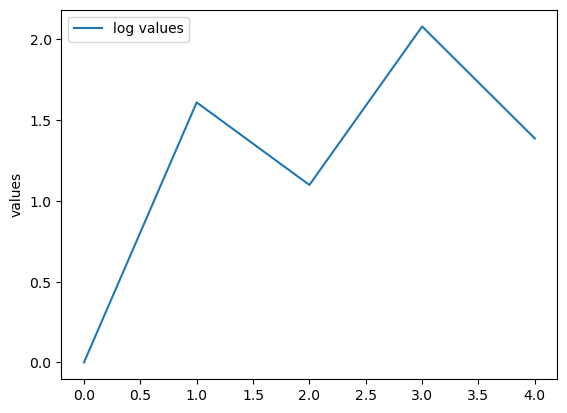

data = pd.Series([1,5,3,8,4], name='values')

sns.lineplot(np.log(data), label='log values')

For today, an issue that’s relevant to all fields of programming, but especially significant in the research world. As a reminder, I’ll post one tiny example per day with the intention that they should only take a couple of minutes to read.

If you want to read them all but can’t be bothered checking this website each day, sign up for the mailing list:

and I’ll send a single email at the end with links to them all.

Imagine a little analysis script like this, which plots the logs of a few data points:

In the real world we would probably not use all three packages, but it works as an example. A more realistic example of a scientific analysis workflow would probably involve more dependencies including obscure packages, specific Python features, and command line analysis tools.

If you email this script to a collaborator, they might try to run it and discover it fails because something is missing, or (worse) it runs but gives different results because package versions changed.

The core problem is: the code doesn’t say what it needs. It works only if the reader guesses the environment correctly.

An improvement would be to add a comment to the start of the script:

This gives the reader a chance to set up the required dependencies before running the program. Even better would be to put the list of dependencies in a readme file, as this is more likely to be seen by users who are not confident programmers and thus unlikely to look at the Python code.

Although a comment or readme will make it possible for the user to figure out what packages are required, it doesn’t help much with the actual setting up. The eventual user of the script will still have to type out or copy and paste the package names. To get round this, Python has the convention of a requirements file, called requirements.txt, that offers a very simple way to specify and then install dependencies. For our script, the file might look like this:

numpy

pandas

matplotlibJust a very simple list of packages, one per line.

This is a great improvement over the commend/readme solution, as it makes it very easy for the user to install the required packages. Package managers like pip and others can parse this file, so setting up the environment can now be done with a single command line:

But there is still one problem: the list of dependencies makes no mention of versions. This means that the user might end up with an older version of the package than you (if they already have it installed) or a newer version (if there has been a new release since you installed it yourself).

This is a particular problem for scientific code, for a number of reasons. Firstly, in scientific code we are very concerned with reproducibility - we would like for collaborators and readers to be able to reproduce our analysis exactly, which might be hard if there are subtle differences between package versions.

Secondly, packages and tools that are used for research often change their behaviour frequently, since the nature of research work is that our requirements rarely stay the same throughout a project.

Thirdly, in scientific Python we tend to rely on a stack of packages (pandas/seaborn/numpy/matplotlib/etc) that all interact in various different ways, so it’s quite easy to run into incompatibilities between different versions of packages in this stack, even though they would all work fine idividually.

There is a very simple fix for this. In our requirements.txt file we are allowed to specify versions of packages as well as their names. All we have to do is add the version numbers like this:

numpy==1.26.4

pandas==2.2.3

matplotlib==3.9.2so pip knows exactly which versions of each package to install.

We can even be a bit more flexible with partial versions:

numpy~=1.26

pandas~=2.2

matplotlib~=3.9The above will allow pip to install whatever the latest version of numpy is that starts with 1.26. This allows for small updates to the pinned version, while hopefully preventing changes in behaviour.

One more time; if you want to see the rest of these little write-ups, sign up for the mailing list: